Alzheimer's disease and potential treatments

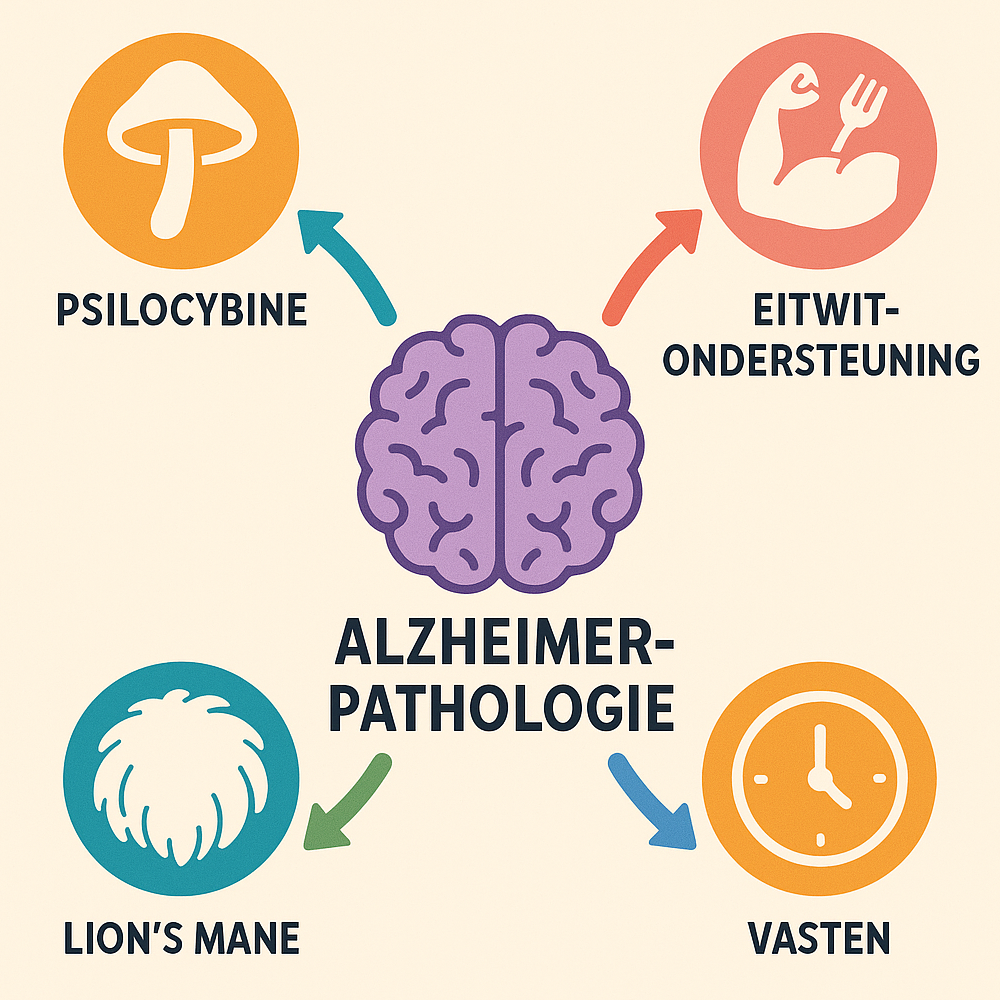

Alzheimer's disease is a neurodegenerative disorder in which brain cells progressively die, leading to memory loss and cognitive decline. Despite available medications, there is a need for new strategies that treat disease processes slow down or reverse. An integrated approach - in which psilocybin therapy (psychedelic support), Lion's Mane (Hericium erinaceus, a medicinal mushroom), protein and amino acid support (including stimulation of neurotrophin factors such as BDNF) and fasting (intermittently or periodically) combined - could provide synergistic effects on brain health and Alzheimer's. In this post, the mechanisms of operation of each of these components discussed, along with existing evidence (primary clinical, secondary preclinical) for their effect in neurodegeneration. We also analyze the overlap and potential synergy between these interventions - both biological (e.g., shared signaling pathways and Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor BDNF, anti-inflammation, neurogenesis) as well as practical (e.g., fasting in preparation for a psychedelic session).

Psilocybin in Alzheimer's disease

Mechanisms: Psilocybin (from magic mushrooms or truffles) is a psychedelic substance that is converted to psilocin in the body. It acts on serotonin (5-HT) receptors in the brain, especially the 5-HT₂A receptor, and promotes neuroplasticity - the brain's ability to form and reorganize neural connections. Activation of 5-HT₂A receptors by psilocin initiates a chain (via a.o. mTOR and CREB signaling pathways) that stimulates the expression of genes for neuronal growth, including the production of BDNF (Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor).. BDNF is an important neurotrophin that promotes the growth, survival and differentiation of neurons. In addition, there is a striking mechanism: psilocin appears to Binding directly to the BDNF receptor TrkB (high affinity, similar to LSD), allowing it to activate BDNF signaling pathways independently of serotonin. This dual mechanism (indirectly via 5-HT₂A as well as directly via TrkB) leads to enhanced neurotrophic efficacy.

As a result, psilocybin stimulates the formation of new synaptic connections and branching in the brain. In preclinical studies, a single dose of psilocybin has been shown to induce in mice within 24 hours a ~10% increase in number and size of dendritic spines (protrusions on neurons that form synaptic connections) in the frontal cortex - and this effect held at least one month on. This indicates rapid as well as sustained synaptic remodeling under the influence of psilocybin. Indeed, in vitro studies show that various psychedelics (including psilocin, DMT) induce neurite outgrowth and spin formation via BDNF/TrkB-dependent mechanisms. Also neurogenesis (the production of new neurons) may be slightly affected by psilocybin: in mice, a slight increase in neurogenesis was seen in the hippocampus after low doses of psilocybin (high doses paradoxically showed a decrease). Although psilocybin is not known primarily as a neurogenic agent, its strong effect on neural plasticity (reshaping existing networks) clearly established. In addition, animal models show that psilocybin can lower inflammatory markers in the brain and reduce oxidative stress, suggesting that it can also anti-inflammatory acts on neuroinflammation (a factor in Alzheimer's disease).

Clinical and preclinical evidence: Most clinical studies with psilocybin to date have focused on mood disorders (such as depression and anxiety in cancer) and not directly on cognition or dementia. Nevertheless, the findings are relevant: psilocybin therapy leads in depressed patients to improved mood, less anxiety and greater cognitive flexibility, which may indirectly support quality of life and cognitive functioning in the elderly. Because approximately 40% of Alzheimer's patients struggle with anxiety or depression, and conventional treatments are often inadequate in this regard, psilocybin is now being investigated as a means to reduce the neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Johns Hopkins University, for example, has started a clinical trial of psilocybin in people with mild cognitive impairment or early Alzheimer's, to see if it can reduce depression and existential anxiety in this population. Although cognitive improvement is not the primary endpoint, researchers hope that the neuroplastic boost of psilocybin can also positively influence the disease process.

Direct clinical evidence for cognitive improvement by psilocybin in Alzheimer's is still limited, but there is evidence in case reports and open-label use. Triptherapie.nl - a Dutch organization offering psychedelic sessions - reports, for example, that they have recently counseled clients with neurodegenerative disorders (such as early-stage Alzheimer's or Parkinson's) in guided psilocybin sessions. This explicitly targets increasing BDNF during the session and reducing psychological stressors. The rationale is that it increase BDNF levels possibly helps slow neuronal deterioration and support repair mechanisms, while simultaneously achieving therapeutic insights and stress reduction (after all, chronic stress exacerbates neurodegeneration). Trip therapy does stress that medical contraindications are carefully ruled out - for example, certain medications (e.g., antidepressants, antipsychotics) cannot be combined with psilocybin. Interest is also growing in science: a recent review mentions psychedelics "Promising as new therapeutics in Alzheimer's disease", not only to improve mood but also because of their molecular effects on inflammation and protein aggregation. In summary, psilocybin acts as a powerful booster of neuroplasticity - via BDNF/TrkB signaling and serotonergic cascades - making it an interesting candidate for neurodegenerative disorders where synaptic connections and neurotrophins are deficient.

Lion's Mane at Alzheimer's

Lion's Mane (wig mushroom) fruiting body on a tree stump. This medicinal mushroom contains compounds (erinacins, hericenones) that stimulate nerve growth factor (NGF) release and possibly promote BDNF.

Mechanisms: Lion's Mane, also known as wig mushroom, is an edible medicinal mushroom that has been used for centuries in Asia to promote nerve health. Modern analysis shows that Lion's Mane contains unique bioactive compounds - particularly hericenones (in the fruiting body) and erinacines (in the mycelium)-which are capable of the blood-brain barrier pass and modulate the production of neurotrophins in the brain. In particular, Lion's Mane is known to stimulate nerve growth factor (NGF), a growth factor crucial for the maintenance and survival of cholinergic neurons (the nerve cells that degenerate first in Alzheimer's). Erinacin A from the mycelium, for example, has been shown to be a highly potent stimulator of NGF production. By increasing NGF, Lion's Mane activates the TrkA receptor (the NGF receptor) on neurons, which downstream ERK/CREB-signaling pathways that promote neuronal growth and survival. The net effect is support of neurite outgrowth (offshoots of nerve cells) and synapse formation. Interestingly, Lion's Mane is not limited to NGF; studies suggest a broader pan-neurotrophic effect. Indeed, certain isolated compounds from Lion's Mane (e.g., hericene A) also stimulate other growth factor pathways in culture cells: blockade of TrkB (the BDNF receptor) could only partially prevent their neurite growth effect, implying that Lion's Mane also BDNF-related routes activates in addition to NGF. In vivo experiments confirm this: mice fed Lion's Mane extract showed increased expression of both NGF and BDNF in the brain, along with improved learning performance and memory. Lion's Mane additionally has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties: it reduces neuroinflammatory responses in animal models (e.g., fewer proinflammatory cytokines in the brain) and thus may protect nerve cells from damage. This combination of properties - NGF stimulation, modulation of BDNF, and anti-inflammation - makes Lion's Mane particularly interesting as a nootropic and neuroprotective intervention.

Evidence in neurodegeneration: Although research on Lion's Mane is relatively new, the results so far are promising. Animal models: In models of nerve damage and dementia, Lion's Mane shows clear effects. In rodents with experimental nerve lesions, Lion's Mane accelerates the regeneration of peripheral nerves and restoration of muscle function. In Alzheimer's disease mouse models (e.g., transgenic mice with amyloid plaque formation), treatment with Lion's Mane improved memory and reduced pathological features such as plaque burden and neuronal degeneration. These preclinical data show that Lion's Mane has neuroprotective effects both functionally (behavioral tests) and biologically (tissue analysis). Human studies: Despite their small scale, initial clinical studies indicate a consistent direction. A double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT in Japan in older adults with mild cognitive decline (MCI, a preliminary stage of dementia) reported significant cognitive improvements due to Lion's Mane. Participants (50-80 years old) took 3 grams of Lion's Mane per day for 16 weeks. From week 8, there was a markedly higher cognitive test scores in the Lion's Mane group compared with placebo, an effect that became even stronger at weeks 12 and 16. After stopping intake, the score dropped slightly again after 4 weeks, suggesting that continued intake is necessary for perpetuation. Crucially, no significant side effects occurred.

In addition, a pilot study in Alzheimer's patients conducted with a special erinacin-A-enriched Lion's Mane mycelium supplement. In this small 49-week trial in people with mild Alzheimer's saw improvements on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE, a cognitive test) compared with placebo, as well as better scores on activities of daily living. This implies that the participants who received Lion's Mane became less dependent in daily functioning over the study year. Although this study was limited in scope, it is noteworthy that a dietary supplement had a measurable effect after almost a year - something consistent with the idea that Lion's Mane is especially useful in long-term use can slow cognitive decline. Other small studies support the cognitive and mood benefits of Lion's Mane: for example, one trial found that healthy middle-aged adults experienced slight improvement on a cognitive test after 12 weeks of ~3.2 g of mushroom powder per day. Furthermore, in two placebo-controlled studies, Lion's Mane reduced the gloomy mood and anxiety in menopausal women (4 weeks of cookies at 2 g/day) and in obese patients (8 weeks, 550 mg/day as part of a diet), respectively. Interestingly, the latter was accompanied by a change in blood levels of pro-BDNF (the precursor of BDNF), confirming that Lion's Mane affects neurotrophic pathways in humans as well.

The preliminary conclusion is that Lion's Mane cognition-supporting and neuroprotective effects, both in healthy individuals and in people with MCI or early dementia. Triptherapie.nl therefore classifies Lion's Mane among the "medicinal mushrooms" and notes that thanks to elevation of NGF, this mushroom can help "Against Alzheimer's and MS (neurodegeneration)". Lion's Mane is also safely and legally available as a supplement, which facilitates practical integration into a treatment protocol.

Proteins and amino acids in Alzheimer's disease

Background: By "protein support" here we mean ensuring sufficient building blocks and growth factors for the brain. In neurodegeneration, there is often a deficiency of certain nutrients or endogenous factors necessary for neuron maintenance. For example, it has been shown that in Alzheimer's patients, levels of BDNF (a crucial growth factor) are reduced. BDNF supports the production of new brain cells and repair of damaged neurons, and chronic BDNF deficiency is associated with accelerated neuron degradation and cognitive decline. It has even been suggested that long-term low BDNF production may play a role in the development of Alzheimer's, Parkinson's and Huntington's disease. The stimulating BDNF (and other neurotrophins) is therefore an important target in new therapies. Classic ways to increase BDNF include physical exercise, cognitive challenge and calorie restriction - but the previously discussed psilocybin and (possibly) Lion's Mane also intervene. In addition, certain nutrients and supplements can positively affect BDNF.

Amino acids and nutrients: For building new synapses and neurons, amino acids - the building blocks of proteins - are indispensable. A good protein supply through diet is crucial, especially in the elderly (who are often at risk for malnutrition and muscle deterioration). Protein-rich foods provide a continuous supply of amino acids such as glutamine, arginine, serine, etc., which are needed for repair processes in the brain. Some amino acids have additional specific effects: tryptophan for example, is the precursor for serotonin and melatonin (both relevant to brain function and sleep rhythm), and sufficient tryptophan can indirectly support mood and neuroplasticity. Another example is L-serine - research suggests that supplementation of L-serine may be neuroprotective, possibly by counteracting excitotoxic substances in the brain. For example, in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease, addition of L-serine to the diet reduced memory impairment. Small clinical studies with L-serine in neurodegenerative diseases (such as ALS and an inherited neuropathy) show improved clinical outcomes or slower disease progression, although the translation to Alzheimer's is still under debate. The general idea is that certain amino acids as supplements can protect the brain or promote recovery, be it as anti-excitotoxic agents (serine, glycine) or as antioxidants.

Ergothionein - a special amino acid: Worth mentioning is ergothionein, a sulfur-containing amino acid found in mushrooms (and thus Lion's Mane). Ergothionein is considered a potential "vitamin-like" substance seen for its powerful antioxidant and cell-protective properties. The human body has a specific transport system for ergothioneine, suggesting that it plays an important role in tissue protection. Triptherapie.nl devotes a blog post to the psilocybin + ergothionein combination against cognitive decline, noting that ergothionein, according to research can slow aging processes in the brain and lower the risk of Alzheimer's and other diseases. Interestingly, ergothionein is often combined with melatonin is called: the combination of melatonin (a hormone/antioxidant) and ergothionein has been shown to inhibit neurodegeneration (including Alzheimer's pathology) in animal studies. Psilocin (derived from psilocybin) has a molecular structure similar to melatonin. From that analogy, Triptherapy poses the question: could the combination of psilocybin (as a melatonin-like substance) with ergothionein perhaps counteract cognitive decline and depression?. Although hypothetical, the idea is obvious that psilocybin's neuroplasticity and ergothionein's antioxidant protection can enhance each other's effect. Other micronutrients can also support BDNF or neuroprotection: omega-3 fatty acids (DHA), for example, increase BDNF expression in the brain, and polyphenols from food (e.g., flavonoids in cocoa, anthocyanins in blueberries) are known to stimulate BDNF and fight inflammation. For example, blueberry polyphenols directly increase BDNF levels, allowing the brain to create new connections. Therefore, a diet rich in vegetables, berries, nuts, fish and whole-grain proteins - as in the Mediterranean or MIND diet - correlates with a lower risk of cognitive decline, presumably in part through these mechanisms.

BDNF stimulation as a strategy: In summary, in Alzheimer's disease, it makes sense to use a variety of avenues to improve the neurotrophins increase and make sufficient "building blocks" available. This can be done through targeted lifestyle choices (proper diet, supplements, exercise) that promote BDNF/NGF. Tripforum emphasizes that a lack of growth factors such as BDNF contributes to neurodegeneration and that restoration of BDNF levels a key factor is in possible delay or reversal of diseases such as Alzheimer's. In our context, psilocybin acts as a potent acute BDNF booster, Lion's Mane as a daily source of NGF/BDNF stimulation, and a protein- and antioxidant-rich diet (including ergothionein) as support to facilitate neurosynthesis and cellular health.

Fasting: metabolic improvement and neuroprotection

Mechanisms: Intermittent fasting - for example, periodically not eating for several hours to days, or a daily eating window (such as 16 hours of fasting, 8 hours of eating) - causes various beneficial stress responses in the body. During fasting, metabolism switches from glucose burning to fat burning, in which ketones released as alternative fuel for the brain. This "metabolic switch" activates cellular maintenance programs: the insulin sensitivity increases, increased autophagy up (cells clear away waste products and broken proteins) and the production of antioxidant enzymes increases. In animal studies, it has been repeatedly shown that calorie restriction and fasting lead to less oxidative damage, less chronic inflammation and improved vascular function. All of these factors play a role in the aging process and specifically in neurodegeneration. Importantly in the brain, fasting constitutes a "mild stress" that elicits adaptive responses: for example, in experimental animals we see that fasting increases the number of synapses in the hippocampus, the expression of BDNF increases learning and memory capacity. Dr. Mark Mattson, a leading researcher in the field, describes that intermittent fasting increases the CREB/BDNF pathway in the adult hippocampus activates, thereby promoting neural connections and neurogenesis. A well-known adage is that fasting engages an ancient survival mode in which the brain becomes sharper and more resilient to compensate for food deprivation - something that biologically translates into increased neurotrophins and synaptic plasticity.

Relevance to Alzheimer's: Alzheimer's disease is characterized by pathological accumulation of proteins (amyloid plaques and tau clusters) and by chronic inflammatory and metabolic problems in the brain. Fasting addresses several of these aspects. Compared to unrestricted feeding, animals on calorie restriction have less β-amyloid accumulation in the brain - one of the core features of Alzheimer's disease. In mouse models, fasting also decreases abnormal tau phosphorylation and glia activation, which together indicate inhibition of the neurodegenerative process. A recent study showed that cycles of a fasting-nabbing diet (FMD, a few days of very low calories) in mice the brain less inflamed made, amyloid-beta and phospho-tau lowered and cognitive performance improved. In other words, fasting activates cleaning and repair mechanisms (such as autophagy) that clean up toxic protein aggregates and keep synapses healthy. In addition, vascular health is known to be essential in dementia (poor blood flow exacerbates Alzheimer's). Intermittent fasting improves the endothelial function and increases the production of ketones, which form more efficient brain fuels and provide neuroprotective signals. For example, ketones (such as β-hydroxybutyrate) act as epigenetic regulators that have anti-inflammatory and BDNF-enhancing effects. There is even research on how the brains of Alzheimer's patients utilize ketones as an alternative energy source; fasting could benefit here by bypassing the energy trap (glucose hypometabolism).

Human data: Although long-term fasting in people with Alzheimer's has not yet been studied on a large scale, there are encouraging initial data. Epidemiological sees that populations with traditional diets and lower caloric intake are less likely to develop Alzheimer's disease. In clinical context, mild interventions have been examined: a 5-day-a-month fasting-nabbing diet was tested in patients with mild cognitive impairment or early Alzheimer's disease. This approach was found to be safe and feasible; patients were able to sustain monthly fasting periods, no dangerous weight loss occurred, and metabolic marker improvements suggested that the mechanism was working. There were indications (still preliminary) that cognitive scores remained stable or improved slightly over several months, but further study is needed. Dr. Valter Longo (who developed FMD) stresses that people should only do this under medical supervision, but that initial results suggest that such a diet is "has biologically beneficial effects that could potentially inhibit disease processes". Meanwhile, short-term interventions in healthy adults are informative: intermittent fasting leads to weight loss, better insulin levels and often an improvement in executive functions (such as working memory and mental acuity), which is plausibly via BDNF-driven plasticity.

Practical application and advice: Many experienced therapists and psychonauts recommend integrating fasting into a holistic health plan. Triptherapy's own "anti-depression diet," for example, recommends that in addition to a healthy diet, you should also fasting regularly. Even part-time fasting (e.g., eating only between 12:00-18:00) for several weeks can provide noticeable improvement in mental resilience. The underlying idea is that fasting helps the body cleans and reset, allowing both body and mind to benefit from greater balance. Specifically for psychedelic therapy, it is common to use the day of a psilocybin session to fast or take only a very light meal. An empty stomach allows the psilocybin to be absorbed faster and more evenly and Minimizes the chance of nausea or vomiting during the trip. Experienced users often fast at least 4-6 hours prior to a psychedelic trip to intensify the experience - in fact, low blood sugar levels seem to be the subjective deepen effects of the trip. (Should someone still want to end the trip early, the trick is precisely to ingest sugar and food to dampen the effects.) In summary, fasting offers significant benefits in both the long term (preventative, neuroprotective) and short term (session preparation).

Synergy of the parts

Given the above effects, there is clear overlap in mechanisms of action of psilocybin, Lion's Mane, protein/BDNF support and fasting, suggesting that a combination could potentially synergistic benefits. In Figure 1 below, we have summarized the main points of leverage of each of the four components and indicated where they complement each other.

| Mechanism / Pathway | Psilocybin (high-dose) | Lion's Mane | Protein/Amino acids & BDNF | Intermittent fasting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDNF increase & TrkB activation | Yes - strong increase BDNF via 5-HT₂A and direct TrkB binding. | Yes - indirectly; increases NGF in particular, but also BDNF modulated. | Yes - goal is to boost endogenous BDNF (e.g. via diet, supplementation, exercise). | Yes - fasting increases BDNF in hippocampus (animals); human plausible. |

| NGF rise & neurogenesis | Possibly mild; no direct NGF effect known. Neurogenesis ↑ at low dose (mouse). | Yes - strong NGF production (erinacins activate TrkA); stimulates neurogenesis in models. | Indirect - sufficient building blocks (Serine, etc.) needed for neurogenesis; some supplementation (e.g. Lion's Mane, omega-3) ↑NGF. | Possible; fasting activates autophagy, may improve neural stem cell environment. Evidence in animal models of ↑ neurogenesis. |

| Inflammation inhibition & oxidative stress ↓ | Yes - psilocybin reduces pro-inflammatory cytokines (preclinically) and lowers stress hormones. | Yes - Lion's Mane is anti-inflammatory (less microglia activation) and antioxidant. | Yes - amino acids such as ergothionein are powerful antioxidants; adequate protein and micronutrients support immune system. | Yes - fasting reduces chronic inflammation and oxidative damage; increases cellular repair. |

| Synaptic plasticity & learning | Very strong - promotes synapse formation and connectivity (dendrite growth ↑); improves cognitive flexibility. | Moderate - promotes synaptic functions via neurotrophins; improves memory in animals and MCI patients. | Indirect - BDNF stimulation and amino acids → improved conditions for synapse formation; e.g. omega-3 improves synapse membranes, polyphenols ↑ blood flow. | Moderate - fasting increases focus and stimulates LTP processes in brain; ketones give clarity. In animals, improved learning performance. |

| Psychological effect | Hallucinogenic experience + therapeutic breakthroughs; stress and depression reduction (therapy-associated). | Not psychoactive; may mildly reduce anxiety and depression with chronic use. | Not psychoactive; protein-rich diet supports mood (e.g., tryptophan → serotonin). | Not directly psychoactive; initially possible feeling of hunger and mood swings, in time often improved energy and mood (euphoria after ketosis). |

Figure 1: Overview of overlapping mechanisms of action of psilocybin, Lion's Mane, protein support and fasting in relation to neuroprotection.

Table 1 shows that BDNF elevation is a common target: psilocybin provides a potent, acute BDNF spike, Lion's Mane also increases secondary BDNF via NGF, and fasting leads to a more gradual BDNF increase. Thus, a combined application could result in persistently elevated BDNF levels, which is essential for synapse maintenance and neurogenesis. Moreover, psilocybin and Lion's Mane complement each other in terms of neurotrophins: psilocybin focuses on BDNF/TrkB, Lion's Mane on NGF/TrkA. Together they can cover a broader spectrum of growth factors than each individually - this is also called the Stamets Stack (after mycologist Paul Stamets), which combines psilocybin microdosing with Lion's Mane to maximize both BDNF and NGF. Indeed, surveys report that a large proportion of microdosers (up to 39%) adds Lion's Mane to their psilocybin microdosing regimen, hoping to enhance its cognitive and neuroprotective effects. Theoretical "could Lion's Mane's NGF boost complement the BDNF boost of psilocybin, providing additional stimulation of synaptic growth". Trip therapy confirms this view, but also cautions that it is still speculative and not clinically proven - so some caution remains necessary.

Also in the area of inflammation and oxidative stress the interventions work complementarily. Chronic neuroinflammation contributes to Alzheimer's disease, and all four components have anti-inflammatory properties: fasting reduces systemic inflammatory markers, Lion's Mane suppresses microglial activation, psilocybin appears to modulate immune cells via serotonin receptors and lower stress-related inflammation, while amino acids/antioxidants (such as ergothionein and glutathione precursors) trap free radicals. Synergy example: Trip therapy suggests that edible mushrooms full of antioxidants (ergothionein, ergosterol, polysaccharides such as lentinan) and hallucinogenic mushrooms (psilocybin) "could theoretically work synergistically and make psilocybin even more effective to biochemically combat depression due to inflammation". In other words, the anti-inflammatory effects of dietary mushrooms plus the neuroplasticity of psilocybin together would address both the cause (inflammation) and effect (neuronal function loss) of depression and cognitive decline. Although this needs further study in practice, it is logically plausible and forms the basis of an integrated treatment vision.

Practical synergy: In addition to biological interactions, there are practical aspects where interventions interact. For one thing, Fasting serve as preparation on a psilocybin session: it cleanses the body, increases ketones (which may make the psychedelic experience brighter) and reduces the likelihood of nausea during the trip. Fasting might even increase the intensity of the psychedelic experience, which may be desirable in a therapeutic setting for deeper breakthroughs. Second, it offers Lion's Mane a continuum of support: where psilocybin is administered occasionally (because of its strong acute effect), Lion's Mane can be taken daily to between the psilocybin sessions by providing neurotrophic support. For example, one can take Lion's Mane (and possibly other supplements such as B vitamins, omega-3s and antioxidants) daily in the weeks leading up to and following a psilocybin experience in order to bring/keep the brain in a "plastic state." This is exactly what Trip Therapy employs: they combine the healing properties of psychedelic mushrooms with lifestyle recommendations (such as nutrition and supplements) before, during and after the session, in their own words with "unprecedented good results". From their perspective, not only do psychedelic hallucinogenic mushrooms, but especially the medicinal edible mushrooms and healthy lifestyle along to improve mental and cognitive health.

Moreover, protein support (proper nutrition) can offset any drawbacks of fasting: after fasting, it is important to regain adequate nutrient intake. Within an integrated protocol one could, for example, after a psychedelic session - done in a sober state - take a recovery meal rich in protein, amino acids and complex carbohydrates can be used to provide the brain with the necessary building blocks for synapse formation (when BDNF and NGF levels are high). This is consistent with the principle that "neuroplasticity window" should be exploited to the fullest: after interventions that increase plasticity, the environment (physical as well as mental) is crucial for the actual embedding of new connections. Adequate nutrition, as well as things like good sleep and cognitive stimulation, are part of this.

Finally, there is synergy in the psychological dimension: psilocybin can provide emotional breakthroughs and spiritual insights that reduce stress and depression; fasting and meditation can improve mindset and focus; Lion's Mane can subtly lower anxiety and gloom over longer periods of time; and a healthy diet full of key amino acids and fats supports the biochemical side of well-being (e.g., enough cholesterol for myelin sheaths, enough tryptophan for serotonin). All of these aspects combined contribute to a more optimal brain environment that are resilient against neurodegeneration. Although formal studies testing all four interventions simultaneously are (still) lacking, available data and practical experience suggest that "the whole is more than the sum of its parts."

Experiences and conclusion

There is a growing movement, both in science and in the user community, that explores this kind of combined approach. Blogs like Triptherapie.co.uk and discussions on Tripforum.co.uk show that "biohacking" with mushrooms, diet and fasting is no longer an obscure idea, but a real approach that people report benefiting from. For example, participants on Tripforum with mild memory complaints report that microdosing with psilocybin plus Lion's Mane improved their concentration and made "brains less foggy"-something in line with a scientific observation that older microdosers who took psilocybin + Lion's Mane + niacin scored better on psychomotor tests than microdosers without those additivesnature.com. Such results inspire further research. Of course, we must remain level-headed: Alzheimer's is a complex disease and no existing drug (including this one) is a complete healing. The interventions outlined here should be seen as potentially retarding or supporting (in English though disease-modifying mentioned).

The synergistic protocol we proposed, with a central psilocybin session surrounded by lifestyle interventions, is an example of integrative medicine for the brain. It combines old and new wisdom - from fasting traditions to cutting-edge psychedelics. Crucially, the four pillars reinforce each other: psilocybin opens the door to neuroplasticity and psychological well-being, Lion's Mane and proper nutritional status ensure that that open door leads to sustained structural improvements, and fasting keeps pathological stimuli (amyloid, inflammation) out as much as possible. As trip therapy's motto goes: "It is not only the magic mushroom that can help us, but also the lifestyle around it "triptherapie.nl.

The next steps would ideally be for clinical trials to test this multi-modal approach in controlled settings. Until then, individuals under expert guidance can already experiment within safety parameters. The preliminary testimonies and scientific rationale give hope that this synergy will at least the quality of life of people with (incipient) Alzheimer's disease may improve, and possibly slow the progression of the disease.

Sources:

G referencing trip therapy forum: Psilocybin & LSD increase BDNF productiontriptherapie.nl; BDNF deficiency role in neurodegenerationtriptherapie.nl.

H referencing lion's mane studies: MCI trial cognitive improvementpubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govpubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov; mild Alzheimer's disease pilot MMSE improvementpmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

J referencing ergothioneine synergy: Psilo + ergothioneine hypothetical against cognitive declinetriptherapie.nltriptherapie.nl.

K referencing fasting and AD: FMD diet lowered amyloid/tau, improved cognition in micebrightfocus.org; 5:2 diet safe in MCI/AD patientsbrightfocus.org.

L referencing microdosing survey: Stamets Stack in older microdosers → better motor scoresnature.com.